Around the General MIDI world in 12 pianos

(last correction: )As friends and followers may know, we* realised at the end of 2022 that we deeply regretted never having learned a musical instrument, and since then we have been having a bit of a music arc. Several, in fact. And somehow, between the autism, an affection for creative constraints, nostalgia, and some happy accidents, this led to us getting very into General MIDI. Perhaps too into it; we now have far too much gear and knowledge from this fading era of music technology, and no idea what to do with it! So… how about we give you a whirlwind tour of the piano tones on the General MIDI instruments we have access to? I promise it'll be fun! Maybe you'll learn something?

(© KeroQ 2010)

Before we begin…

Please let us quickly explain what MIDI and General MIDI are, because we want this post to be accessible to folks with some interest in music who are not informed, or perhaps (as is tragically all too common) misinformed on this topic. If you're already very familiar with both, you can of course skip this section, but I hope it'll be interesting enough that you read it anyway.

MIDI is a fundamental technology in electronic music. Launched in 1983, and still critically important in 2025, it standardises a way for synthesisers and other musical instruments to communicate. The basic idea is that you can take a MIDI keyboard (🎹), and using a MIDI cable, connect it to a MIDI synthesiser. When you depress a key on the keyboard, a small digital message along the lines of “play the note Middle C with a gentle velocity on channel 1” is transmitted over the MIDI cable. When the MIDI synthesiser receives this message, it then produces some kind of sound in response. This may sound like an oversimplification, but it is in fact exactly how MIDI works, and that entire message is encoded in only two to three bytes depending on context — it's frightfully efficient!

Of course, MIDI can do a lot more than encoding the depressing (and of course, releasing) of keys. There's also, for example, a kind of message sent when you turn a knob, push a slider or spin a wheel, used for everything from volume to reverb level to adjusting the ADSR parameters of a synth. There are also some special messages handling esoteric use cases like dumping and restoring synthesiser settings, or updating firmware. But if you think of MIDI as just “tiny digital messages representing pressing a key or turning a knob”, you already understand most of it. In fact, there are many MIDI devices that only use those parts of MIDI, including many popular Digital Audio Workstations (DAWs).

Technically, the “MIDI” we just described is two different things:

- The MIDI data format defines the format for those little messages, like “depress the A5 key very forcefully on channel 2” and “turn the volume knob to 100”.

- The MIDI physical interface is those “MIDI cables”, the “MIDI ports” they connect to, and the rules for how they need to be wired up electrically to actually be able to transmit those little messages.

This distinction matters because eventually they became separated. The classic MIDI ports and MIDI cables are less common in 2025, now that USB and Bluetooth and virtual cables inside of DAWs are alternative options. Similarly, the MIDI data format has found uses outside of these “cables”. Every DAW uses the MIDI data format internally for all sorts of purposes, for example. But even in a pre-DAW world, there was another kind of “MIDI” you will have heard of:

- Standard MIDI File (SMF, but you probably know it as just “.mid” or “MIDI files”) is a file format for storing MIDI messages with timestamps. It's the same “release the E3 key on channel 5” and “turn the volume knob to 50” stuff, except slightly modified to “on the third beat of the fourth measure, release the E3 key on channel 5” and “on the first beat of the first measure, turn the volume knob to 50”. Again, this is not an oversimplification (though the timestamps are more precise than this).

At this point, if you've been using computers for a long time, you're probably thinking of some beloved (or hated) MIDI files, right? Among the ones bundled with Windows, PASSPORT.MID is a personal favourite of ours:

(Synthesized by our Roland SC-7, direct feed recording.)

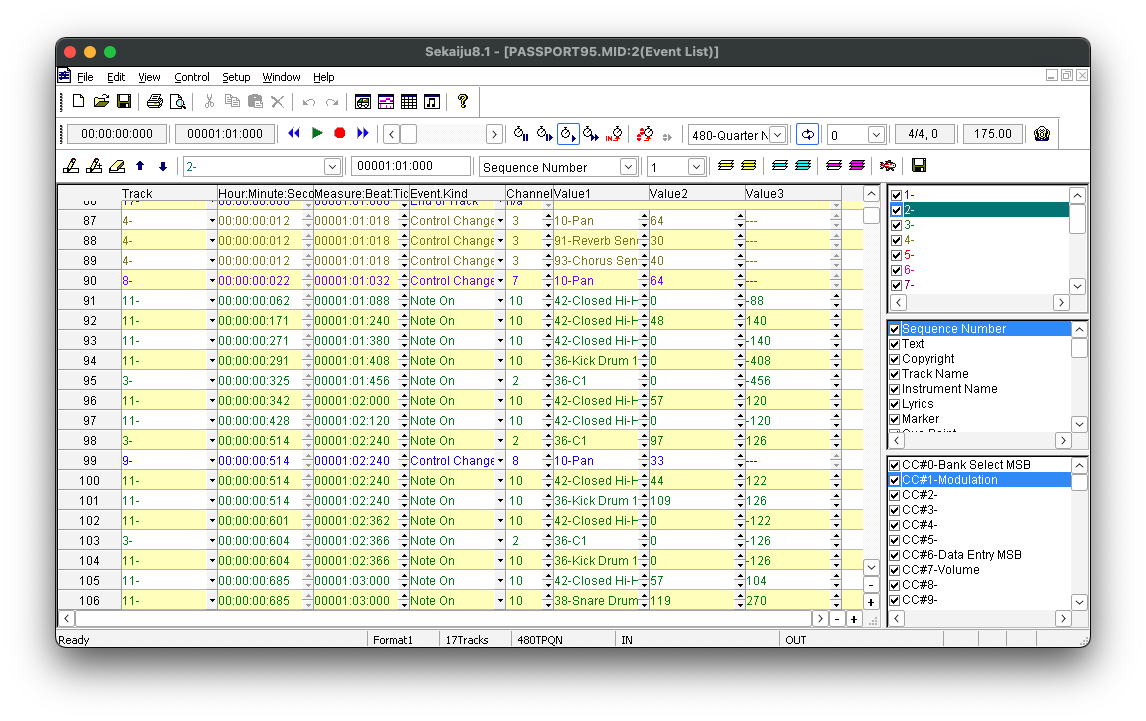

And indeed, PASSPORT.MID (and CANYON.MID, ONESTOP.MID, mm2wood.mid and god only knows what else) are Standard MIDI Files, and if you look inside them with a MIDI editor, you'll see the content is indeed just simple little messages:

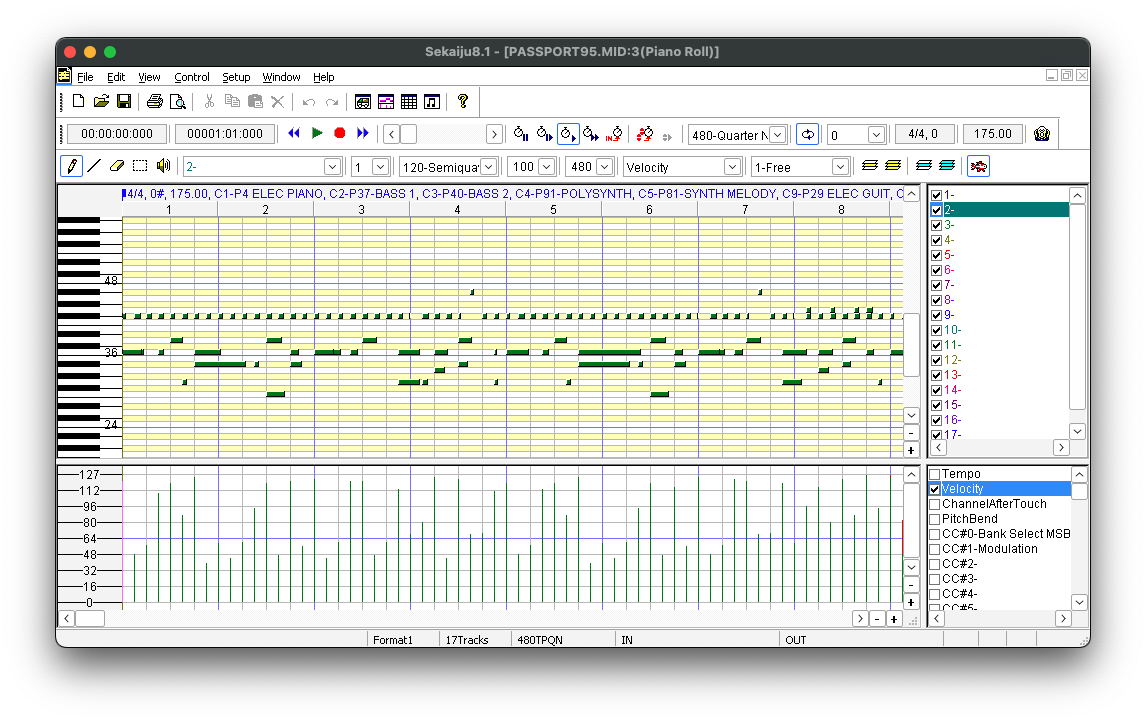

Alas, the event view in this particular MIDI editor isn't the easiest to read. Of course, it can also be presented in a more musically meaningful way:

But, and this is quite important, these are not just any old MIDI files. They are specifically MIDI files that comply with General MIDI, the final thing that must be explained. The MIDI technologies previously mentioned allow controlling synthesisers, and they even allow recording and replaying performances (in the form of MIDI data), but crucially, none of those standards stipulate what MIDI data is supposed to “sound like”. The MIDI standards do of course stipulate a few things, like how the keys on a piano should be numbered, and a few common “controllers” (the knobs/sliders/wheels mentioned earlier) like volume and panning. However, they don't say what particular kind of instrument sound a synthesiser should produce, or in fact even require it to produce a sound at all — there are many compliant MIDI devices that don't make sounds, believe it or not! And so:

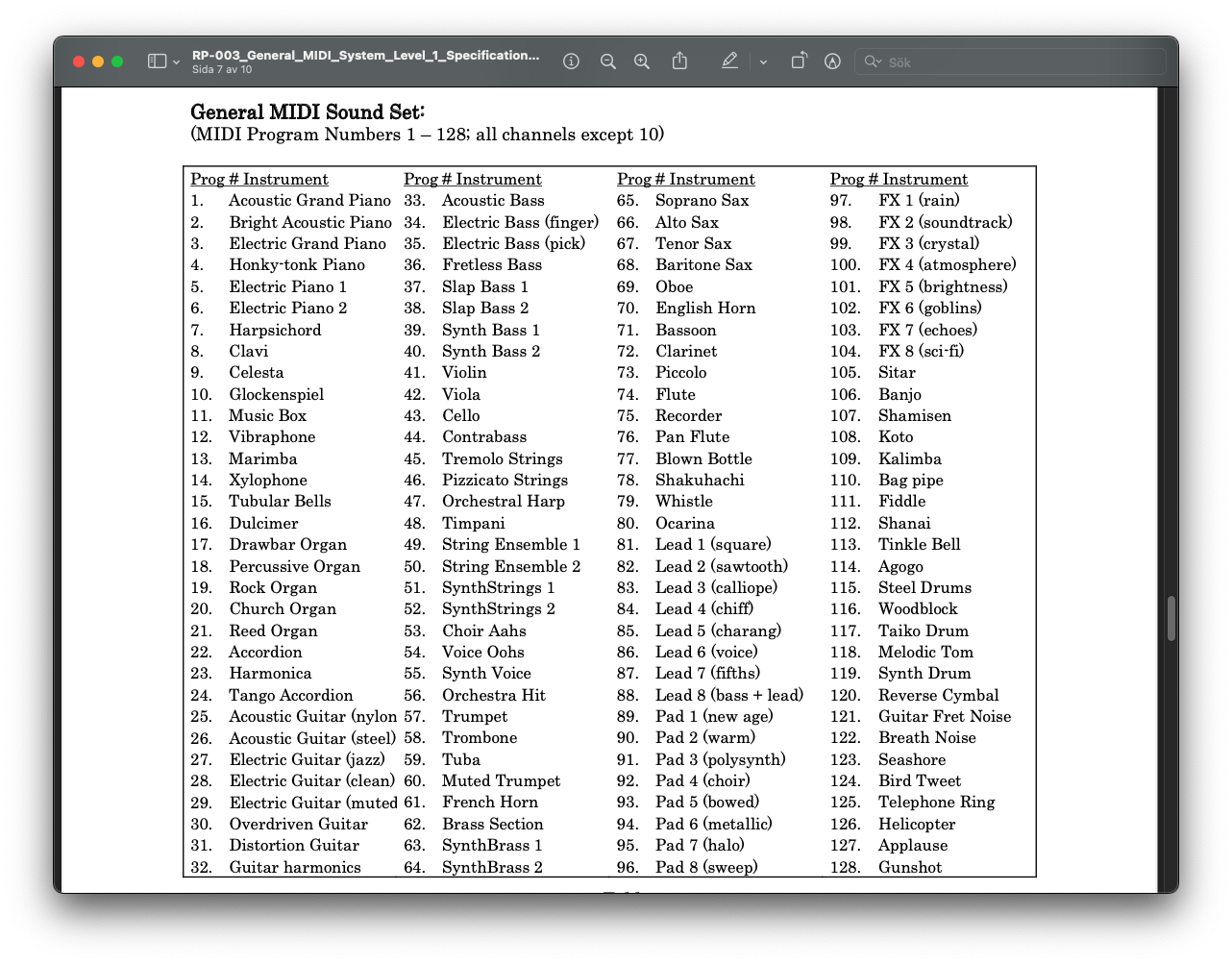

- General MIDI is a standard from 1991 that contains a set of basic requirements for synthesisers. They can be summarised as: “can play at least 24 notes at once, with multiple instruments, in stereo”. It also contains a standardised list of 128 instrument sounds (plus some drum sounds) that such a synthesiser should support.

And unlike all the other MIDI stuff mentioned, General MIDI is a legacy technology, a thing that was born, grew, peaked, fell, and died… all more or less within a single decade, the 1990's. It is a failed dream, not forgotten, but not always fondly remembered. It does technically still exist today in a few places, but only as a shadow of what it once was, a niche for the nostalgics.

…But you wanted to hear the piano sounds, right? Well, let's get back to that. If you were following so far, the only other technical detail you need to know about General MIDI beyond this point is that instrument number 1 (or 0, depending on how you count) is the “Acoustic Grand Piano”, that there is a “set the instrument on this channel to instrument number 1” message, and that the standard says nothing more about what it ought to sound like. :)

Roland, the king of General MIDI

With that out of the way, let's look at some General MIDI synths and their piano tones. There will be four categories: Roland, Roland again, Roland but this time as farce, and finally Yamaha. They are all Japanese, and they are mostly Roland. This is not just because hikari_no_yume has a particular fondness for Japanese products and perhaps especially for Roland products, though we could never deny the accusation. It is because General MIDI was a very Japanese invention, and more specifically, a Roland invention. Moreover, the only companies that really managed to keep up with Roland there were Japanese (Yamaha, and perhaps Korg to a lesser extent, though we know less about them; Casio also made a decent attempt early on). This does not mean the General MIDI world was limited to Japanese companies, not by any means. There might be hundreds of General MIDI synth vendors out there, and for example, the Android phone in your pocket has an obscure General MIDI software synth — for ringtones! Roland and Yamaha were simply the best and most influential, and took the General MIDI concept places few others could.

The demo MIDI file (is also Roland)

The file you'll be hearing over and over again in this post is called 04PIANO.MID, whose proper title is “Prologue”, © 1999 Roland Corporation. It's a demo file included with the Roland-ED Sound Canvas SC-8850 from 1999, the highest-end dedicated General MIDI synthesiser Roland ever produced. Generally speaking, demos for high-end General MIDI synths play back terribly on older ones. For example, they are likely to use fancy new MIDI messages that older synths won't recognise (as does this demo). But this demo is just a single, relatively simple piano part, and piano is such a critical instrument that even if a General MIDI box can barely manage anything else, it will still try to sound good at piano!

It should also be pointed out that General MIDI is of course designed for multitimbrality, that is, playing a large arrangement with several kinds of instruments at once. Playing back a simple MIDI file that only contains a piano part is, I suppose, not in the spirit of General MIDI, especially since every General MIDI product ever has been forced into a quantity over quality tradeoff by virtue of having to support those 128 standard instruments. And yet, we find ourselves enjoying General MIDI pianos nonetheless, and we think there's a special charm to them.

In any case, armed with a piano-only MIDI file from the end of the General MIDI era, we shall travel back in time to where it all began…

The Roland Sound Canvas SC-55

- Release year: 1991 (original version); 1993 (mkII)

- Summary: The original and most influential General MIDI synthesiser, the reference and comparison point for all things General MIDI.

- Am I supposed to have heard of this thing? If you care about the history of recorded music, especially electronic music, particularly computer music in the 1990's, and definitely if you have any interest in 1990's PC games… yes. We really hope so, anyway. Its influence cannot be overstated.

- Okay, but where have I heard it before? The soundtrack of DOOM (1993) and myriad other games from its era. Also… you will have heard derivatives of its samples in many other things, for reasons you'll perhaps start to see as you keep reading.

- Fun fact: General MIDI is actually a retcon by other musical equipment manufacturers. The very earliest SC-55 units produced did not have the General MIDI logo on them, because they didn't actually support it; the General MIDI standard is based on some kind of leak of what the SC-55 was going to support, and there's actually some small errata that prevent those early units from being fully compatible. Now, why would the other manufacturers do this? Because the SC-55 is not just the first General MIDI synthesiser, it's the first Roland GS synthesiser, which is… Roland's version of General MIDI, and might be described as “General MIDI if it was good”. It has a lot more features in it, such as guaranteed support for reverb and chorus and control thereof, some basic sound editing features (ADSR and filter cutoff/resonance), and something like twice as many instrument sounds. But in 1991, only Roland had the capability to ship a fully realised product that could do all that at a reasonable price. General MIDI was a desperate attempt by other manufacturers to be able to half-compete!

The default Acoustic Grand Piano preset on this thing is called Piano 1 in the manual.

We don't own one, so we don't have a sound sample, sorry. But we do have two of the next-best things…

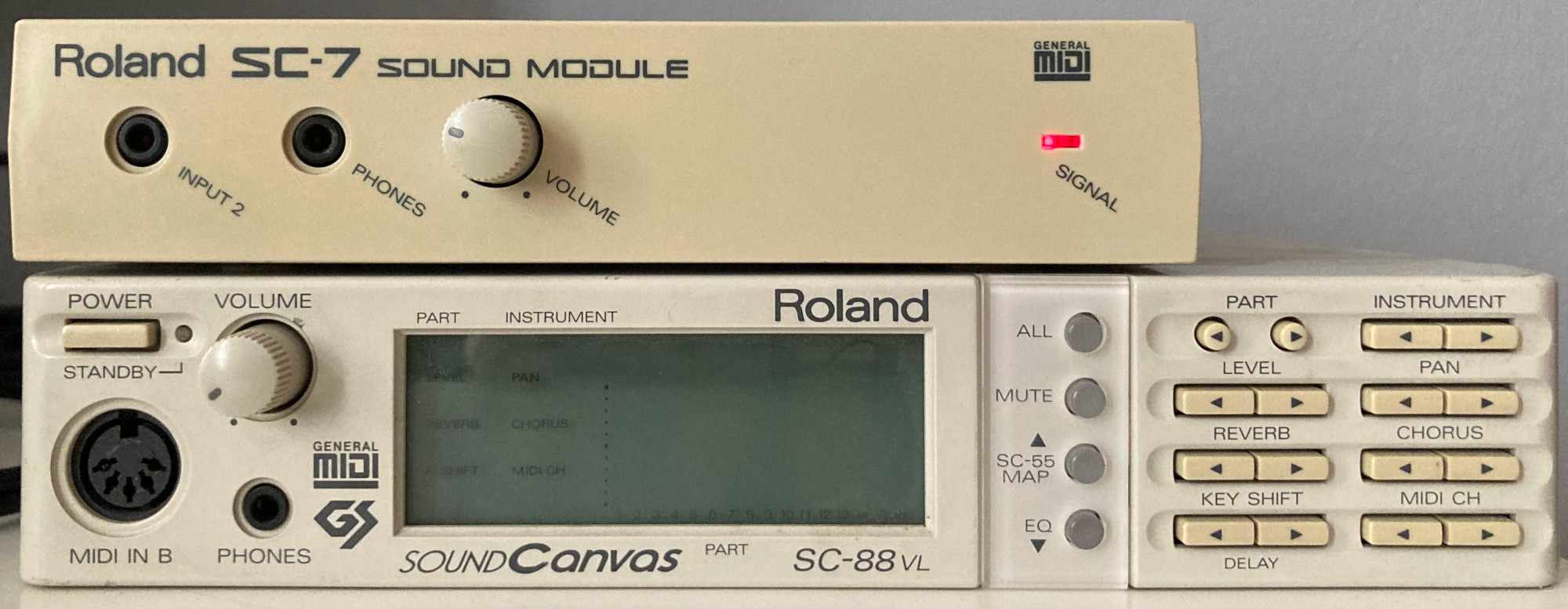

The Roland SC-7

- Release year: 1992.

- Summary: A cut-down SC-55 with most of the Roland GS stuff removed, no controls, no screen, and slightly lower-quality instrument sounds, but still fully compliant with (and very good at) General MIDI.

- Am I supposed to have heard of this thing? No, it's a footnote of history, and really quite obscure. We have no idea why it has a Wikipedia article. We love it to bits though!

- Okay, but where have I heard it before? We have no idea if you have heard it before, unless you've like, listened to our music or other attempts by us to convice the world it might be special. However, it sounds a lot like the SC-55, in many cases outright identical, so in a sense you probably have heard it before. The piano tones in particular, though, are not quite the same…

- Fun fact: Did you notice it doesn't actually say “Sound Canvas” on it?

- Not particularly exciting fact: The SC-7 being derived from the SC-55 is a hypothesis with many points of evidence. There is a weird quirk of the SC-55mkII that isn't described anywhere in its manual (filter cutoff being disabled for a specific set of patches), but it is described in the SC-7 manual, and if you test it, you find that it applies to the same patches on both.

And finally, our first piano audio sample…

We really love this piano sound, even if it's very unrealistic. It's just so charming.

This is a direct feed audio recording. Everything you hear, including any effects (reverb and so on) is from the audio output of the SC-7, and the SC-7 is solely being controlled by data flowing into the “MIDI IN” port on the back. Of course, a MIDI player is being used to “play back” 04PIANO.MID on our laptop — but all it does is send those MIDI messages at the designated times, over a traditional MIDI cable. Every subsequent audio sample will be using this same type of setup.

(click here only if you want to read gnarly signal chain details)

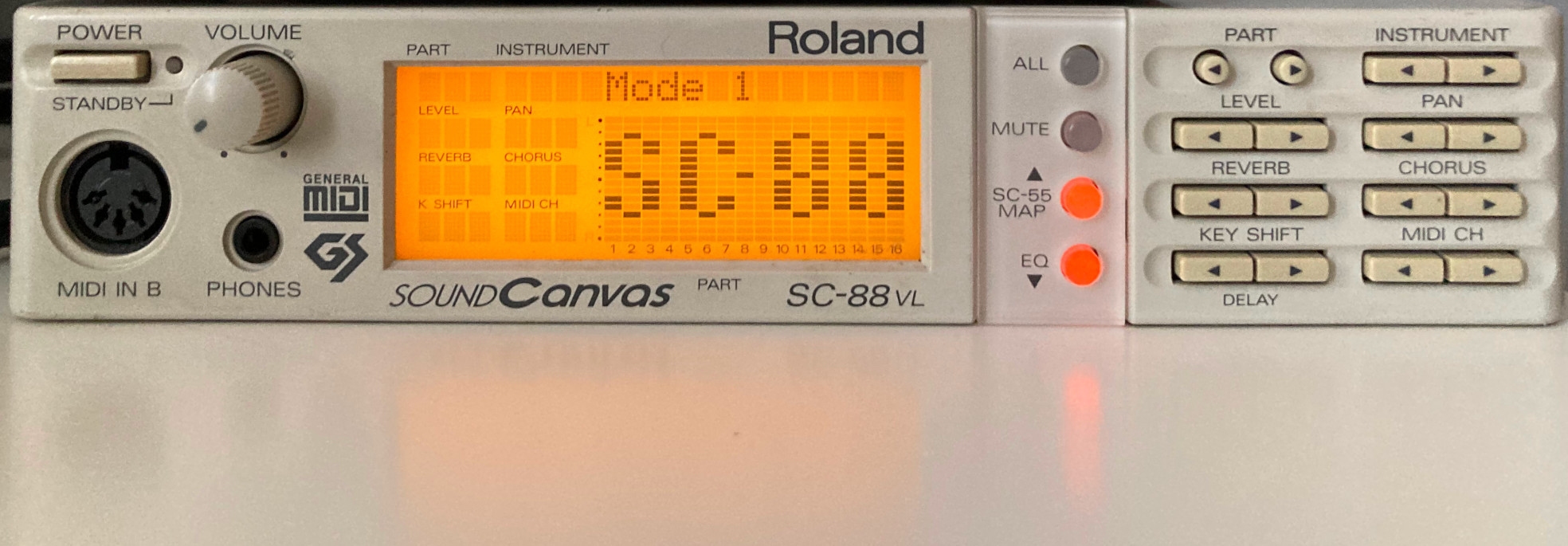

The Roland SC-88 (…and its cuter variant)

- Release year: 1994 (Roland SC-88), 1996 (Roland SC-88VL, which is just the SC-88 in a smaller, cuter package).

- Summary: The first big upgrade to the SC-55: twice the polyphony, twice as many parts/channels, the addition of EQ and a delay effect (complimenting the existing reverb and chorus), many new instrument and drum sounds (with many of the 128 General MIDI sounds now being completely different), and various synth engine improvements.

- Am I supposed to have heard of this thing? If you care about 1990's General MIDI hardware? Yeah. If you care a lot about the particular tools used by composers of 1990's Japanese video game music? Yeah. Otherwise, probably not.

- Okay, but where have I heard it before? Probably in some 1990's Japanese video game soundtrack. Super Mario 64 is allegedly an example, but of course it uses its own sample playback engine, so it only has samples of the SC-88's samples. There are definitely games with Red Book CD Audio where you can hear this thing in its full glory however.

- Fun fact: It has a “SC-55 map” button. As you might imagine, this makes it switch to a mode where it tries to sound like the SC-55, but it does not do so perfectly (a new DAC, big changes to the behaviour of the synth engine, and a few samples being cut from the ROM to save space all contribute to this).

So here's our SC-88VL trying to sound like the SC-55:

If you compare that to the SC-7 example and try to imagine some kind of midpoint between them, you'll get what the SC-55 sounds like, I guess.

And here's our SC-88VL trying to sound like, well, itself:

A lot darker, right? We were never too fond of it, but I think it's growing on us.

(click here only if you want to read gnarly signal chain details)

Same as the SC-7 case, except:- MIDI: MacBook → (USB) Steinberg UR22mkII → (MIDI) Roland SC-88 “MIDI IN A”

- Audio: Roland SC-88 “PHONES” jack (3.5mm) → cheap 3.5mm TRRS to TRSS cable (goobay article number 63826) → Roland SC-7 “INPUT 1” (and then the SC-7 signal chain as normal — yes, we are using the SC-7 here not as a synth but as a mixer because our audio interface only has two inputs and we are lazy, it works for us and it is a purely pass-through analogue type thing, there's no round-trip DAC-DSP-DAC fun in a 1992 budget product, we know it probably adds a tiny bit of noise but we don't hear it and don't care)

The Roland SC-88 Pro

Despite the name, and the fact it looks almost identical to the SC-88 (the big one, not the cute SC-88VL we own), the SC-88 Pro was anything but a minor upgrade, and has to be talked about in its own right.

- Release year: 1996 (same year as the shrunk-down SC-88VL).

- Summary: It's just an SC-88, but… stuffed with tons of really cool new sounds pulled from other Roland product series, and with one of those Boss (Roland's guitar effects brand) guitar multi-effect engines slapped in there, so now you can have real (not sampled) guitar distortion and whatever else. …if, that is, you use the latest version of Roland GS, of course. This stuff never made it into any revision of General MIDI, of course. Not even General MIDI 2 (a thing we have been avoiding mentioning because it came out too late to ever be relevant).

- Am I supposed to have heard of this thing? If you care about 1990's General MIDI hardware? Please tell me you have heard of the SC-88 Pro. It's really quite important. If you care a lot about the particular tools used by composers of 1990's Japanese video game music? Please tell me you have. It's really quite important. Otherwise, probably not.

- Okay, but where have I heard it before? In Japanese video game soundtracks of the time, even moreso than the non-Pro. The SC-88 Pro is very beloved and with good reason. We don't have the best examples on hand, but we will include the obligatory Tsukumo Hyakutarou shoutout. We must also mention that the most famous Touhou game, Embodiment of Scarlet Devil, has an SC-88 Pro version of its soundtrack if you use the MIDI option, but you're probably more familiar with the pre-rendered “WAV” soundtrack, which sounds a bit different. According to this forum post, the SC-88 Pro versions were written first, and the WAV version is the the result of ZUN rearranging the songs for a different synth.

- Fun fact: This is the only Sound Canvas generational leap that didn't create compatibility problems. The SC-88 Pro is, true to its name, good at sounding like an SC-88.

But we don't have an SC-88 Pro, so no audio sample here, sorry.

The Roland-ED SC-8850

The pièce de résistance?

- Release year: 1999.

- Summary: The last serious entry in the Sound Canvas series, the most powerful of them all, and also the first one with an actually pleasant control scheme. It adds even more sounds, it adds even more compatibility headaches with yet another synth engine revamp and weird changes to the sample set, and it does some things that annoy SC-88 Pro enthusiasts, but it's still an overall superior product in most ways.

- Am I supposed to have heard of this thing? If you care about 1990's General MIDI hardware? Please tell me you have heard of it. Otherwise? No.

- Okay, but where have I heard it before? No idea. We imagine there are probably plenty of Japanese composers who loved it, though. Actually, I think someone figured out that the GameCube startup jingle might have been composed with it, but I will not claim to have proof.

- Fun fact: It has a patch where, depending on how hard you play the keys, it plays different “jazz” scat/acapella samples. Do-dat-dah! Oh, and it has this newfangled “USB” thing, so you can connect it to your iMac.

We do not own one of these, but someone on YouTube who goes by “Romantique Tp” (the name of an infamous Roland trumpet patch used in Touhou game soundtracks, not found in the Sound Canvas series, but present in the closely related Studio Canvas series…) uploaded a recording, and we have to let you listen to the SC-8850 demo MIDI on the SC-8850 itself, right? So here is their recording:

Now that's a pretty piano.

Roland (pro mode)

Lest we convince you the Sound Canvas series is the only series of Roland synthesisers that matter, it really is not. There are an unfathomable number of series of Roland synthesisers, let alone models, even if you “only” count the ones that happen to be ROMplers released in the 1990's. Within that context, the Sound Canvas series' market positioning was consumer to prosumer. So what does a true pro product look like?

Well, naturally there are also an unfathomable number of pro Roland synthesisers. But one of the big ones is:

The Roland JV-1080

The history of the Roland JV series is a real mess, so we'll spare you the details. This thing is not even the first JV, but it is the one famous enough to have a Wikipedia page:

(We don't own one, these things are terrifyingly big.)

- Release year: 1994.

- Summary: A major upgrade to the JV series, this is an absolute beast of a professional rack-mount digital synthesiser (specifically, a ROMpler). It makes the SC-88 from the same year look like a toy! I mean, the SC-88 doesn't let you create totally custom new instrument patches by tweaking hundreds of parameters, it doesn't let you expand the built-in sounds with an endless series of very expensive expansion cards that Roland are all too happy to sell you, it doesn't have anywhere near the same level of quality of built-in sounds, and it doesn't even have multi-effects. (Of course, the SC-88 Pro did bring multi-effects and a nice selection of lower-quality JV-ish sounds to the SC series two years later, but…)

- Am I supposed to have heard of this thing? If you care about electronic music production technology? Yeah. At least if you care about the 1990's.

- Okay, but where have I heard it before? Music produced in the 1990's and (in its later incarnations) early 2000's, and to some extent to this day (Roland never stopped recycling sounds from it). Not just video game music. Music. As it happens, we are incredibly fond of the Phantasy Star Online soundtrack, which reportedly was largely made on a JV-2080, the JV-1080's identical-sounding successor. We didn't know this when we got a JV for ourselves, so you can imagine our delight when we instantly recognised several of the built-in patches!

- Fun fact: Roland reward you for your purchases of expansion cards by giving you huge stickers that say “EXPANDED” to plaster all over the façade, just in case anyone didn't know that you've spent as much on expansion cards as you have on the synth itself. :)

We don't own a JV-1080, because that thing is… like, vertically twice the height of the SC-88VL, horizontally twice the width, we dare not ask about the depth, and we definitely daren't ask about the weight. But we do own its cuter younger sibling:

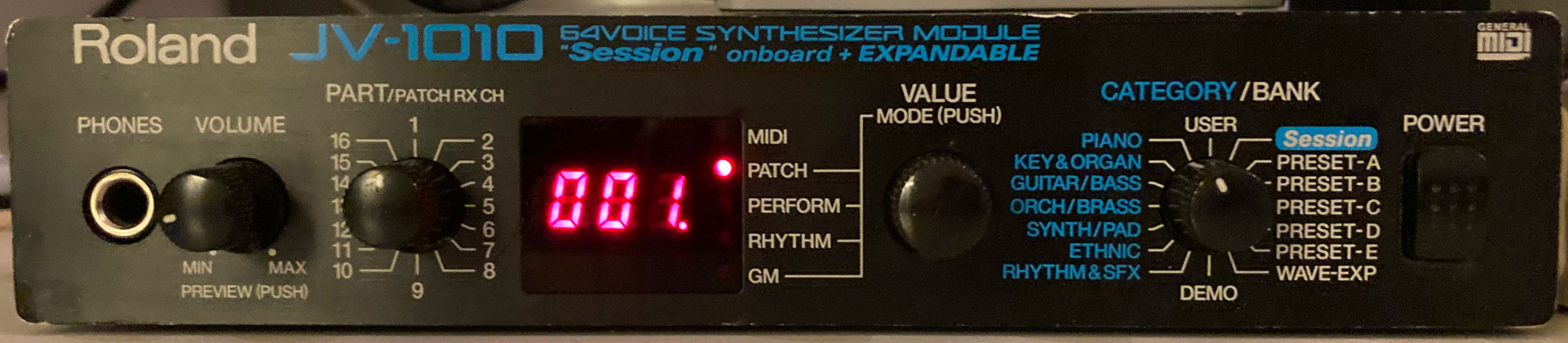

The Roland JV-1010

- Release year: A big hit in 1999!

- Summary: It's a JV-1080, but in a smaller, cheaper package, and with all the sounds from the “Session” expansion board built-in. (It also has all the sounds from the JV-2080, the JV-1080's successor.) If you want to do fancy editing stuff, you need to use a computer because there's no panel controls for it.

- Am I supposed to have heard of this thing? No idea, but since it's just a JV-1080 but smol, it doesn't matter.

- Okay, but where have I heard it before? Ditto.

- Fun fact: Only one expansion slot lmao. How are you supposed to live? Our wallet is dangerously full!

Okay, enough chatter, let's hear how the piano sounds:

Quite pretty, yes? But we're actually sandbagging here. We have been avoiding mentioning that General MIDI on the JV series is something of an afterthought. Professionals don't need General MIDI! Or, more accurately, supporting it well would be a tradeoff, and would come at the expense of things more important to the target market for the JV series. Whereas the Sound Canvas series consists of synths that, essentially, only do General MIDI (and Roland GS, which is “General MIDI if it was good”), the JVs primarily do their own thing, and have a General MIDI mode as a little bonus (and don't even attempt to support Roland GS). But they do have a unique, interesting set of General MIDI sounds, and they're usually higher-quality than their SC counterparts, even though this Piano 1 patch is deliberately trying to sound something like the SC-55's.

Let's briefly leave the world of General MIDI. What does the default JV (or, well, “JV not in General MIDI mode”) piano sound like?

Almost the same, but not quite, right? I think this might even be the same set of samples, but with tweaked parameters within the patch. By the way, it's called 64voicePiano because the JV-1080 (and JV-2080, and JV-1010)'s maximum polyphony is 64 “voices”, and this particular piano patch will let you play 64 notes simultaneously using that budget. Some synth patches use, say, 4 “voices” per note, effectively limiting how many notes you can play at once to 16, but not this one.

But that's the best an unexpanded JV-1080 from 1994 could do. What if you ponied up for the “Session” expansion, filled with high-quality samples of instruments that uh, “session musicians” would supposedly play? Well, then you get this piano:

It's such a refined, elegant sound, and it was why we wanted a JV-1010.

(click here only if you want to read gnarly signal chain details)

Same as the SC-7 case, except:

Roland, but this time as farce

Hopefully the brief excursion outside of General MIDI land and into the world of professional synths was enjoyable, because the next stop on this journey might be less so…

So far, this post has only talked about dedicated hardware General MIDI synthesisers. This is because they always were and still remain the reference point for what General MIDI is supposed to be, its most complete and most enjoyable implementation. Shockingly however, it turns out most people in the 1990's who just wanted to listen to some simple background music in their PC games might not, in fact, have had hundreds of dollars of extra disposable income to spend on the finest General MIDI synthesiser money could buy. They didn't even have the money to spend on a good one. So what did they use?

Well, generally speaking, they used whatever the sound card (or sound chipset) in their computer happened to have available. In the late 1980's and early 1990's, the cheapest option would be a Yamaha FM synthesis chip of some kind, thanks to those being integrated into the AdLib Music Synthesizer Card, the Creative Sound Blaster series, and many clones thereof. We won't say anything bad about FM synthesis, it's a fun technology that produces lovely sounds, but it wasn't well-suited to General MIDI for various reasons. That didn't stop people from trying, of course, because bad music synthesis is better than no music at all! If you remember PASSPORT.MID from earlier, here's what Windows 95's built-in “MIDI Mapper” would turn it into if you only had one of those:

(Pure audio available as a FLAC file… with the same hiccups. ^^;)

Naturally, then, it did not take long before sound card manufacturers started adding newer synthesis technology to sound cards that would be suited to General MIDI. The likes of Roland and Yamaha did join in on this, and if you couldn't afford or didn't want an SC-55 or SC-7, Roland for example would happily sell you what was basically a SC-55 or SC-7 on a card. But these were of course still quite expensive, and various other factors meant they were never going to conquer the PC sound card market anyway. In practice, you would be much more likely to own, say, a Creative Sound Blaster AWE32, which contained a sample-based synthesis engine you could upload a custom sample set to. And while that's, technically speaking, effectively the same type of synthesis as used by the Sound Canvas series, these cards didn't sound anywhere near as good, even if you used the exact same samples. (This is where “SoundFont” comes from, which is not a generic term — it's a trademark owned by Creative — not a good file format, and not something that should have survived the 1990's, but that's a rant for another day.)

And then, as we enter the latter half of the 1990's, people start to realise that having dedicated music synthesis in sound cards is rather silly. For one thing, it's a compatibility headache for music composers, if everyone's computer plays back your music differently. For another thing, everyone has a CD-ROM drive now, and it can play back perfect quality CD audio. And most importantly, as CPUs got faster and computers had more RAM and disk space, it became increasingly practical for the CPU to totally take over synthesis duties, relegating the sound card to a mere digital-to-analogue converter (DAC). Software was inevitably going to eat hardware's lunch at some point.

And well, you'll never guess what company loves it when software eats hardware's lunch…

Microsoft GS Wavetable Synth

“Microsoft GS Wavetable Synth” is a sequence of words that is sometimes hard to utter without scorn, or at least a certain sense of pity. This is, alas, the General MIDI synth we can be absolutely certain you have heard before.

But we should be kind to it, because in 1998 or so, it was probably a big step up for most users who encountered it. Nobody was going to buy a Sound Canvas SC-55 for their office computer intended for Word, Excel, and maybe a side of Minesweeper, right?

(Until 2025-10-04, this post mistakenly claimed this very old about box was gone in modern Windows. Thank you to Catkitty for pointing out our error!)

- Release year: 1998 at the very latest (Windows 98), but the relevant Microsoft press release is from 1996.

- Summary: A very low-fidelity sample playback engine that supports General MIDI, and does it using a licensed Roland Sound Canvas sample set… even if it's a low-quality, bastardised one. Despite the name, it doesn't really support Roland GS, because almost all GS features are conspicuously absent, but it does have the extra instrument sounds at least. Most importantly: if you have any version of Windows released since 1998, you have this thing and its sample set on your computer. It is the default General MIDI synthesiser in Windows. If you double-click on a MIDI file on a Windows computer, Windows Media Player will open, and these days you don't even get a choice, it will always play back the MIDI file using this… thing.

- Am I supposed to have heard of this thing? I wish you weren't.

- Okay, but where have I heard it before? I'm so sorry.

- Weird fact: This thing has too many names. These days it appears as “Microsoft GS Wavetable Synth” in Device Manager and in MIDI software, but it used to be called the “Microsoft GS Wavetable SW Synth” at some point, and the eagle-eyed among you will have noticed the modern about box still calls it both the “Microsoft GS Software Wavetable Synthesiser” and the “Microsoft Software Wavetable Synthesiser”. We keep getting frustrated that people mistakenly “correct” us on its name, but who can blame them when Windows itself is inconsistent. 😭 (Oh, and there's translations. Did you notice that our screenshots use the British spelling of “synthesiser”? Be glad we chose to spare you from Swedish!)

- Fun fact: There is a thriving, if tiny, scene of people who use this thing as a fascinating creative constraint. The works of HueArme (SoundCloud, Twitter) are particularly astonishing. The BotBers have a category for it too.

Anyway, here's that damned piano:

(Recorded on Windows 10.)

If it sounds dry, that's because it is. Microsoft GS Wavetable Synth doesn't have any effects, not even reverb. But all things considered, it does sound kind of nice here.

Since we've already let you listen to two renditions of PASSPORT.MID, we may as well let you hear that, too, just for comparison's sake (especially against the SC-7):

(Recorded on Windows 10.)

But if you have a Windows computer, you could also just, you know. Download that file and double-click on it.

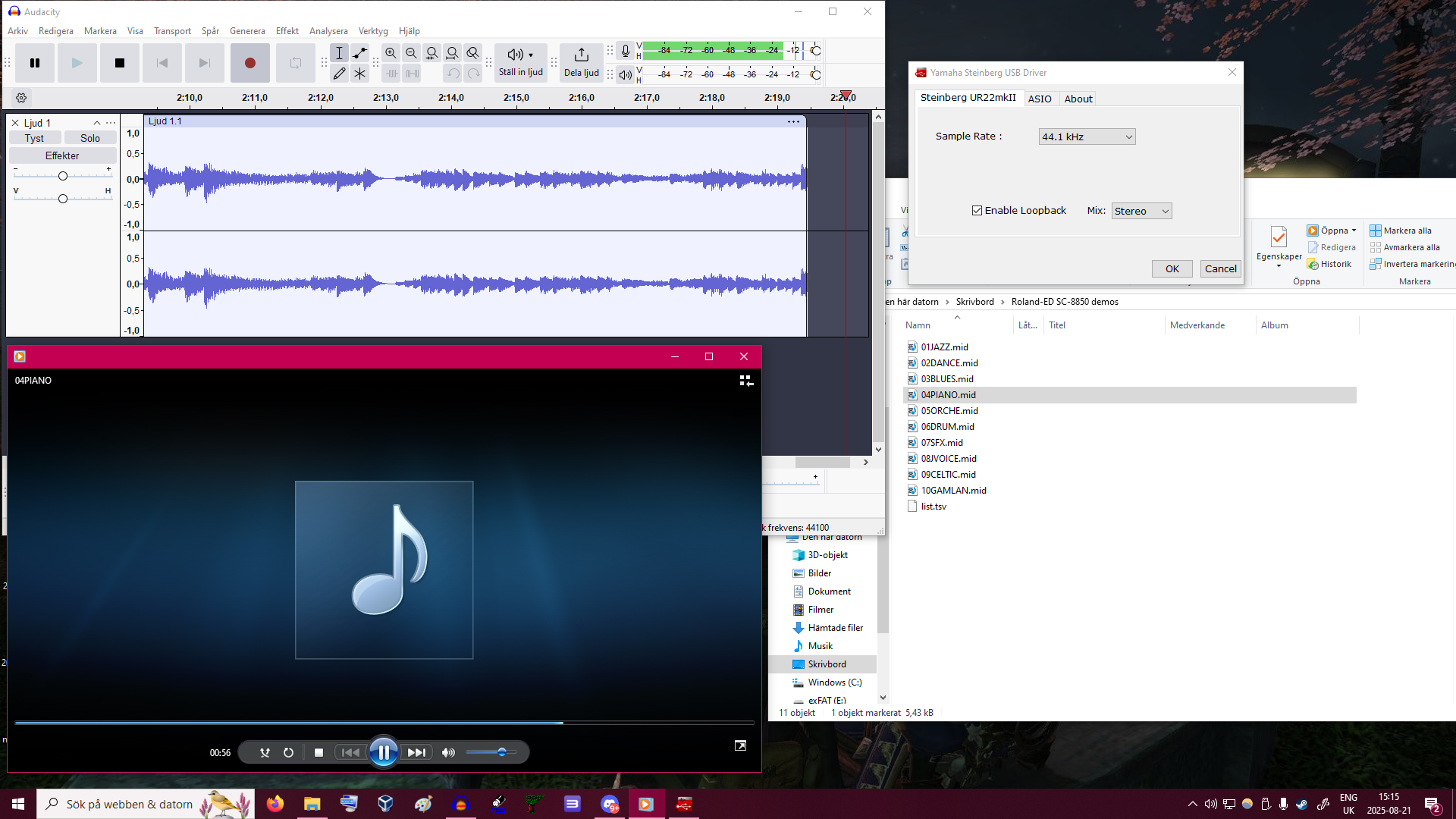

(click here only if you want to read gnarly signal chain details)

MIDI file played back in Windows Media Player on Windows 10. The Steinberg UR22mkII audio interface was configured to loopback mode using the settings. Audacity was used to record. This does mean there's a little bit of background noise, because the actual input to the audio interface is never perfectly silent, and loopback mode doesn't suppress it, it just mixes in the computer's output back into the “input”.

MIDI file played back in Windows Media Player on Windows 10. The Steinberg UR22mkII audio interface was configured to loopback mode using the settings. Audacity was used to record. This does mean there's a little bit of background noise, because the actual input to the audio interface is never perfectly silent, and loopback mode doesn't suppress it, it just mixes in the computer's output back into the “input”.

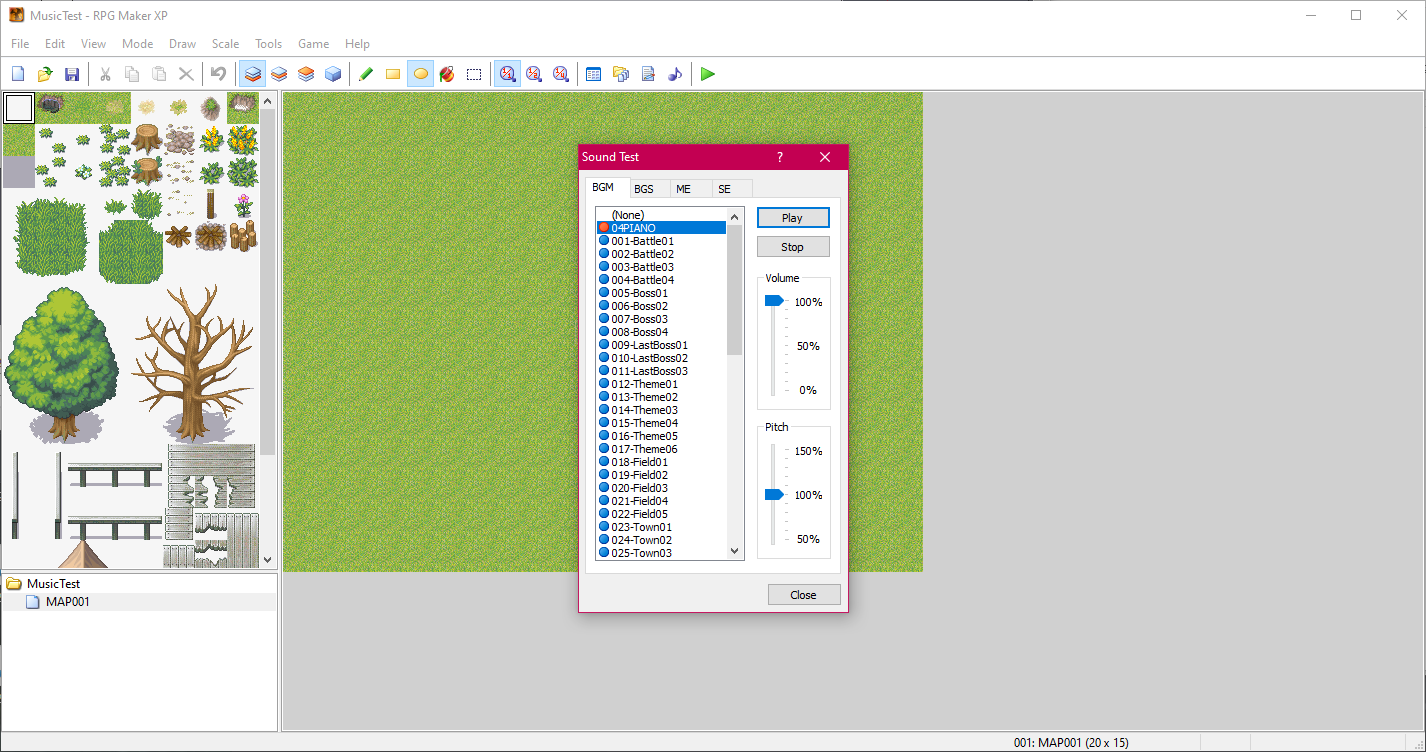

DirectMusic

Windows actually contains two General MIDI synths! Remember Microsoft® DirectX®? It's not just Direct3D and DirectDraw, it's also… DirectMusic!

- Release year: Probably somewhere between 1996 and 1998.

- Summary: Same sample set as Microsoft GS Wavetable Synth, but it at least supports reverb and various other nice features. Unlike Microsoft GS Wavetable Synth, you can load a custom sample set.

- Am I supposed to have heard of this thing? Probably not. Few people seem to realise it exists.

- Okay, but where have I heard it before? RPG Maker XP, games made with it, and perhaps some other games from that era.

- Fun fact: RPG Maker XP comes with some really nice MIDI files like “035-Dungeon01.mid” that sound especially nice on the SC-7 (FLAC version), definitely better than in DirectMusic.

Here's the piano again:

If it sounds… identical aside from the reverb, then that's probably how it's meant to sound!

By the way, the sample set used by both these synths is located at C:\Windows\System32\drivers\gm.dls, so it's often referred to as “gm.dls”. It's in the industry-standard Downloadable Sounds file format (aka DLS; why did SoundFont have to survive instead…), and if you use the right tools, you can look at the patch names, extract the samples, edit the synth parameters, etc. It even contains a textual summary of its content: “226 melodic + 9 drum instruments” (the same number as the SC-55mkII's GS set). Of course, having too much fun here would violate the license found in “gmreadme.txt”. You do care about copyright, don't you?

(click here only if you want to read gnarly signal chain details)

Same process as for Microsoft GS Wavetable Synth, except using RPG Maker XP instead of Windows Media Player.

Core Audio's MIDI synth (the macOS thing)

Microsoft wasn't the only company that licensed a bastardised low-quality Roland Sound Canvas sample set from Roland in the late 1990's. Apple, of course, also joined in on the fun. The history of this is more complicated, because they must have revised it a few times… it was a feature of “QuickTime”, and then when the 2000's came around and Mac OS X replaced the old Classic Mac OS — a fundamental technical transformation, more radical than even the Windows 98 to Windows XP transition — it became a part of “Core Audio”? The point is that modern macOS still has its own equivalent of Microsoft GS Wavetable Synth, with a very similar sample set, and we aren't sure exactly what it's called.

(They show up in the Audio MIDI Setup app.)

- Release year: 🤷♀️

- Summary: Apple's equivalent of Microsoft GS Wavetable Synth.

- Am I supposed to have heard of this thing? No.

- Okay, but where have I heard it before? No idea.

Unlike on Windows, you can't just double-click on a MIDI file on macOS these days; QuickTime no longer supports MIDI. But certain DAWs and other apps on macOS do support the MIDI synth built into Core Audio, including everyone's favourite, VLC Media Player, so here's what that sounds like:

Yeah, this synth also has reverb! Why is it only Microsoft GS Wavetable Synth that doesn't?!

By the way, at least on our macOS Monterey install, the sample set is located at /System/Library/Components/CoreAudio.component/Contents/Resources/gs_instruments.dls. You can glean a little of the history by looking at the text inside the file: the phrases “1997 Roland Corporation” and “QuickTime Music Synthesizer” appear within.

(click here only if you want to read gnarly signal chain details)

VLC has a “Convert / Save…” option that basically plays back a file and, instead of outputting the video and audio to your screen and speakers, renders it into another video/audio format. We used that to convert the MIDI file to FLAC here. But beware that VLC's conversion feature is kind of an afterthought, a legacy of it being originally more of a video streaming app than a “video player”, and therefore it produces quite badly-formed files with, for example, broken length metadata. So, if you do use this feature, you should re-encode the file before sharing it. We of course did that here anyway because of the trimming and loudness normalisation we have been doing for all the piano audio samples.

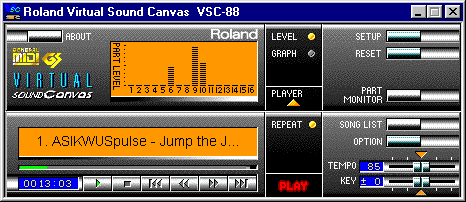

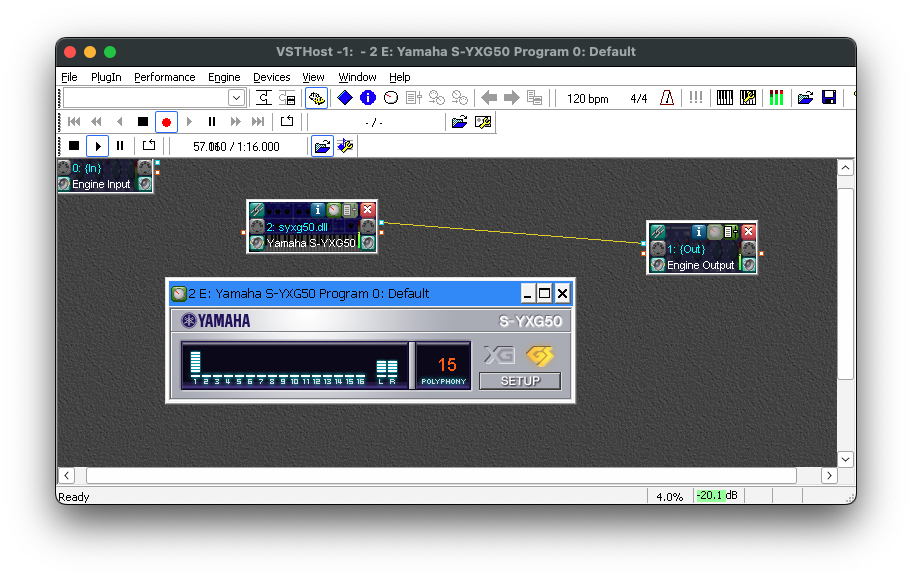

Roland Virtual Sound Canvas

Finally, lest we accidentally convince you that Roland can do no wrong, we should add that they had their own part in the farce that is “bad software implementations of General MIDI”. In the 1990's, they released their own paid commercial product called Virtual Sound Canvas. It sucks, it doesn't follow their own goddamn specifications, it's definitely not worthy of the Sound Canvas name, and it doesn't run on modern versions of Windows, so we can't be bothered to once again go through the hassle of trying to get a recording out of it. But look at it, isn't it pretty:

We must clarify that this is a totally different thing to their (tragically discontinued) “Roland Sound Canvas VA” VST, which is a very good software recreation of the SC-8820 (a close relative of the SC-8850), and easy to recommend if you can somehow obtain it.

Yamaha

At long last, it's time to talk a little bit about Yamaha. Yamaha are a goliath in the music world, bigger and far older than Roland, and active in far more spheres than just electronic music and guitar accessories. For example…

They also make acoustic pianos, saxophones, and drumkits of the non-electronic variety… plus a ton of electronic products! Oh, and golf clubs. There's even a brand of motorcycles called “Yamaha”, but that division is a separate company these days.

Despite all that, Roland were Yamaha's main rival when it came to General MIDI. And while Roland beat them to the punch with General MIDI, Roland GS, and the SC-55, Yamaha were not taking it lying down, and they put in such a strong showing that, arguably, they eventually almost won. It would be unreasonable to talk about General MIDI without giving Yamaha's contributions at least as many words as Roland's, but this post is already too long, so we'll try to avoid too much detail. We will simply invite you to imagine the many things in the Yamaha General MIDI world we are forced to leave out.

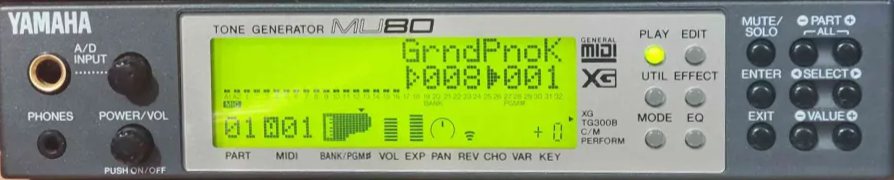

The Yamaha MU80

As we already discussed, the Roland SC-55 from 1991 was not only the first General MIDI sound module, but far better than anything else any other manufacturer could produce for some time after, with Yamaha being no exception. If you're curious, the Yamaha TG100 and Yamaha TG300 are things you can google, and the latter especially was a decent attempt. But the Yamaha General MIDI story really starts to get interesting with this thing, the very first entry in the Yamaha MU series…

- Release year: 1994. Yes, the same year as the SC-88.

- Summary: Yamaha leapfrogged Roland at this point in every respect other than, perhaps, the tastefulness of the built-in sounds. Like the SC-88 it does General MIDI, and it even does Roland GS (but it's called “TG300B mode” to avoid Roland's lawyers). Like the SC-88, it has 64 polyphony, and it has three effects units. Unlike the SC-88, it introduces Yamaha XG, which is Yamaha's idea of “General MIDI if it was good”. And… actually I lied, it has four effects units. Instead of a unit that can only do delay, it has a multi-effects unit, and it also has a dedicated guitar distortion effect unit. That unit is particularly useful when combined with yet another novelty: its “A/D input” (analogue-to-digital input), so you can plug in your electric guitar and jam out with distortion, delay, chorus and reverb (or plug in a mic and karaoke out), all on top of a full MIDI backing track. Roland never added an equivalent feature to the mainline Sound Canvas series!

- Am I supposed to have heard of this thing? If you care about 1990's General MIDI? We really hope so, it's very important. There might be some other contexts where it is relevant too.

- Okay, but where have I heard it before? We don't know, sorry. We don't doubt it got plenty of use, but Roland's samples seem to be a bit more beloved, and we simply have less knowledge here. Of course, this is just the first entry in the MU series, and much of the content has been recycled in many subsequent Yamaha products from the 1990's.

- Fun fact: It even has a dedicated “C/M” mode, which emulates a fairly obscure Roland product, the Roland CM-64, which was a sort of proto-Sound Canvas in some ways. The Sound Canvas series also emulates it, but in a more fragile fashion, and without a dedicated mode. Yamaha were really determined to eat Roland's lunch.

We don't own one of these, but you'll see why that doesn't matter in a moment.

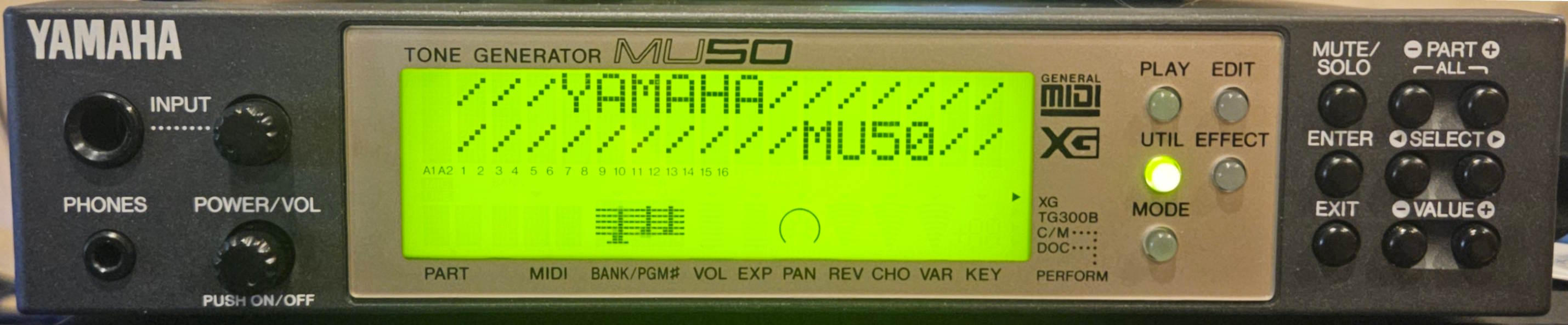

The Yamaha MU50

The next entry in the MU series was actually a step backwards… but quite deliberately. This thing will look quite familiar:

(We don't own one.)

- Release year: 1995.

- Summary: The budget version of the MU80. It set the minimum requirements for Yamaha XG, and it set them far higher than Roland GS, because GS's reference point is a 1991 product (the SC-55), and XG's reference point is a 1995 product (the MU50). An unfair contest, for sure. This thing has half the polyphony (only 32), drops the “A/D” guitar/mic input and dedicated distortion effect unit (the multi-effect unit can still do it, though), and it has a few less sounds. But otherwise, it's more or less the same.

- Am I supposed to have heard of this thing? Same as for the MU80.

- Okay, but where have I heard it before? Same as for the MU80.

- Fun fact: The dot-matrix part of the LCDs on several products in the MU series will, occasionally, display an animated cat-like creature. This is not a documented feature and nobody seems to know what their name might be. They're very cute, though, whatever they are. Off the top of our head, we aren't sure if the MU50 and MU80 have them, but if you want to see them, they pop up a lot in this video of the Yamaha MU15's demo song. (The MU15 is from 1998 and basically a portable MU50.)

We don't own one of these either, but we own something that sounds very similar…

The Yamaha CBX-K1XG

Finally, a hardware product other than a “sound module”! All the SC and MU-series things we've shown you so far have been “MIDI sound modules”. While they're where General MIDI began, and the easiest way to demonstrate it, it's important to understand that that even if we only look at Roland, and even if we only look at the technology in the earliest SC-series product (the SC-55), there were still easily a hundred different products that all had that exact same synthesis engine and sample set, and in every shape imaginable: keyboards, sound cards, dedicated MIDI player appliances, sequencer workstations, grooveboxes, whatever. Many of these products are incredibly obscure! If you want to get a “Roland Sound Canvas SC-55”, it might cost you a pretty penny on the used market. If you want to get a “product with a Roland GS synthesis engine that sounds suspiciously like a Roland Sound Canvas SC-55”, you may get lucky. That's why we own an SC-7, incidentally; too cheap to resist.

Well, that more or less applies to Yamaha too. There are an unfathomable number of 1990's Yamaha products that sound just like the MU50, and we own one such example:

- Release year: 1995.

- Summary: It's a MIDI controller keyboard that also has a full MU50 engine inside it, complete with speakers and the ability to run off batteries. This was marketed as an “all-in-one DTM” solution. “DTM” is a Japanese acronym for “desktop music” (it's meant to sound like “desktop publishing”). These days the best translation of DTM is “DAW user”. But in 1995, it meant using things like the Sound Canvas series, the MU series, and this thing. The point is, you'd buy this if you wanted to make music with your computer, and were only willing to buy exactly one piece of gear. You wouldn't even need a MIDI interface; like most of these old DTM products, it can connect directly to a computer using serial (the old kind, not USB).

- Am I supposed to have heard of this thing? No.

- Okay, but where have I heard it before? Same as for the MU80/MU50.

- Fun fact: The keybed on this thing really sucks, the speakers suck too, and it has the same design language as any cheap computer peripheral of that era, even if the technology inside is pretty great. It has a sibling product, the SK1XG, which is seemingly identical aside from all the labels on it being in Japanese, because it was intended to be sold to Japanese schools. No, Japanese electronic music products from this era don't generally have Japanese labels on them, even for the text displayed on the LCD, if any. They're English-only, even in Japan (but the manual will be in Japanese).

And so, here's the basic piano from this thing:

Yamaha changed up their basic sound set less often than Roland did, so this sound can be a little overfamiliar, but we'll freely admit it sounds quite nice here.

(click here only if you want to read gnarly signal chain details)

Same as the SC-88VL case, except with the CBX-K1XG.

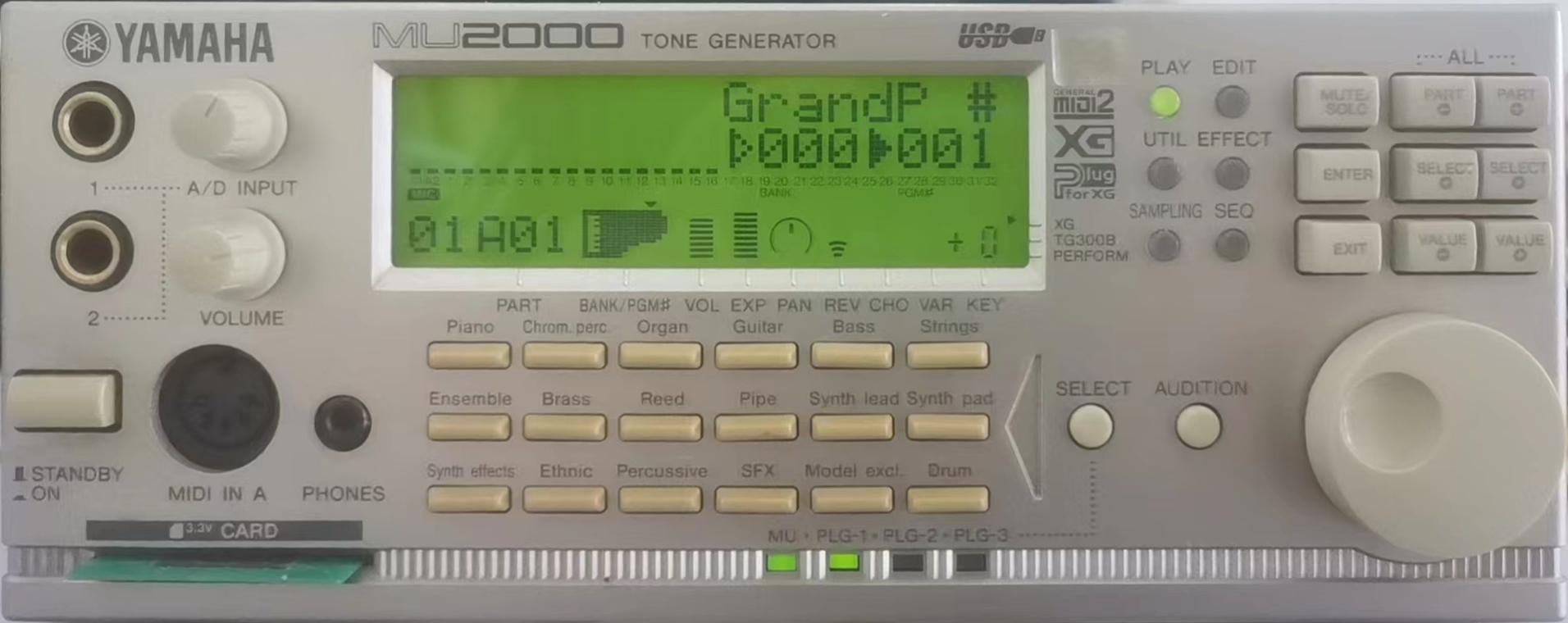

The Yamaha MU90, MU100, MU128, MU1000, and MU2000

You've so far only heard what Yamaha could do in 1994 and 1995, at the very start of the MU series. They didn't stop there: 1996 brought the MU90, 1997 brought the MU100, 1998 brought the MU128, and 1999 brought the MU1000 and MU2000. If we talked about these units, we'd be here all day, because Yamaha really took this to absurd heights. The MU2000, for example, has over 1000 built-in sounds, five multi-effects units, and three expansion card slots that aren't just for adding additional samples and patches — they're for adding entire additional synthesisers, and Yamaha produced several different types of those, including for FM synthesis, virtual analogue synthesis, and a vocal synth that's some kind of predecessor of Vocaloid, among others. And, yes, it's still, primarily, a General MIDI sound module, if you can believe that.

We don't (yet?) own any of those fancy things and don't care to talk about them any more than that, but here's a pretty picture:

The Yamaha QY70

To give you another little taste of the many other things in the world of General MIDI, here's something we actually do own:

- Release year: 1997.

- Summary: A portable synthesiser workstation, or groovebox, or “walkstation”… whatever you want to call it, it's basically a DAW in a box, but without the ability to record or play back audio, only MIDI. It has an elaborate “patterns” system with automatic reharmonisation, like an arranger keyboard's auto-accompaniment styles. Sound-wise, it can do everything the MU50 can do, but it has a bunch of additional instrument sounds that are quite nice, and a lot more drumkits. The user interface is frankly incredible for a portable device of this era, though we found the sequencing aspect specifically to be too clunky for us to really enjoy it.

- Am I supposed to have heard of this thing? No idea, but it seems like it has a cult following among some electronic musicians, and seemingly the kind who actually make music rather than spending 3 days writing a blog post about the history of General MIDI. If you search for “Yamaha QY70” on YouTube, there's tons of folks doing really cool stuff with these.

- Okay, but where have I heard it before? The “Game Corner” theme from Pokémon Diamond & Pearl is very obviously based on the QY70's EuroBt1 (“Eurobeat 1”) preset pattern (audio, MIDI), with the intro in particular being entirely unchanged. (A key selling point of the QY70's MIDI-based pattern/style system is that you can trivially change the tempo, chord root and chord type, so those differences don't count.) We can't be credited with this discovery, but we did go out of our way to help Mudstep when they wondered if someone had a QY70 for this reason. :)

- Fun fact: It makes a sad face when the battery is low. It also makes a happy face whenever an operation completes successfully. Oh, also, in the year 2000 they made a sequel called the QY100, which adds a guitar “A/D input” similar to the MU80, an interesting feature if you happen to be a travelling guitarist for instance.

We're pretty sure the default piano on this sounds just like the CBX-K1XG's, and at this point we are sick of hearing it, so we didn't bother recording an audio sample. That's not its fault, we just happen to have spent a long time making ourselves listen to that one tone in one octave at the highest velocity setting, and that was a mistake. It can also be used for really beautiful stuff.

Yamaha S-YXG50

This post had an entire section complaining about how seemingly nobody in the 1990's could make a good software clone of Roland's General MIDI synths, not even Roland themselves. So you'd think that applied to Yamaha too, right?

Wrong:

- Release year: Sometime in the late 1990's?

- Summary: It's basically a perfect software XG implementation, and it even does GS, officially-licensed too. This of course means it's also a very good General MIDI implementation.

- Am I supposed to have heard of this thing? Probably not, but it's good to know about.

- Okay, but where have I heard it before? Uhh… Battle of the Bits dot com, perhaps? They have a category for XG music made with S-YXG50.

- Fun fact: A variant called S-YXG70 was created specifically for Final Fantasy VII's PC port. Yes, the game with the guy named Cloud who has a big sword. No, that game didn't use General MIDI on the PlayStation. Yes, Yamaha re-arranged the entire soundtrack of the game, nearly a hundred songs, for both Yamaha XG and General MIDI, and shipped a copy of S-YXG70 with the game so you could play it back. Yamaha were, unsurprisingly, very proud of this (and they should have been, because we can't believe they pulled it off so well).

Here's how the piano sounds in it:

See how that sounds almost identical to the CBX-K1XG? That's how you know it's good. :)

The Yamaha PortaTone PSR-350

The MU series and that software plugin are an important part of the Yamaha General MIDI story, but we would be remiss not to talk about the Yamaha PortaTone “PSR” series briefly. This line of arranger keyboards (a particular type of keyboard instrument) is one of the longest and best-selling in the world, in fact they probably are the prototypical do-everything keyboards. You've surely seen one of these before, right?

- Release year: 2001, if the manual is to be believed. But you have to understand, Yamaha have been churning out very similar keyboards to this for literally decades. You could buy something much like it at any point in the late 1990's, or early 2000's, or 2010's, or even the present day. They have modernised in various ways over the years, but it's still roughly the same thing. The second-hand market is flooded with these.

- Summary: It's a keyboard. It's like, the keyboard. It does keyboard things. They had several of a closely related model to this one in the middle school we went to (doubtless they got an education discount), complete with the “DJ” button, and probably the same pre-loaded demo song (the Mission: Impossible theme).

- Am I supposed to have heard of this thing? The PSR-350? No. The Yamaha PSR series? You have heard of it regardless of whether you've “heard of it”. You have definitely seen it in a music store. If you're a keyboardist, you've surely played one at some point.

- Okay, but where have I heard it before? This specific one? No idea. The PSR series? Oh gods. Too many places. It's a bit of a cliché. Apparently a lot of the classic Club Penguin songs were made on a PSR. There is a hyper-popular Brazillian musical duo that begin every song of theirs with one particular PSR preset drum fill (if we're not mistaken). And myriad other examples, probably.

- Fun fact: The “DJ” button that these things had for many years is certainly an… experience? It must have made a generation of music teachers resent their employers' commitment to Yamaha.

These things of course do General MIDI, most of them do something called “XGlite”, and a rare few even do not-lite Yamaha XG. So here's what our demo MIDI file sounds like in the General MIDI mode:

But of course, while General MIDI is not an afterthought on the PSR series — Yamaha really want to be able to sell you, as a PSR owner, MIDI files from their decades-long library of popular music covers — it is still a secondary focus. The purpose of the device is to be an instrument you can just play, and to sound decent while doing it. And since it's a keyboard, the most important instrument sound of them all is the Grand Piano… so important it has a dedicated button, actually:

And so the demo MIDI sounds a little better if we use technical trickery to make it be played back in the “Portable Grand” mode:

We don't know if it's the world's greatest piano sound, but it's the best piano sound on the best keyboard we have, and it's brought us endless joy over the years.

(click here only if you want to read gnarly signal chain details)

Same quarter-inch cable thing as with the JV-1010 case, but with the PSR-350 of course. We did however really, really suffer when trying to record this, because those MIDI hiccup problems on macOS caught up with us, and uh… we had to improvise workarounds, which you can see in the filenames of the FLAC files. :(

The Yamaha PSS-A50

And now for something completely different! We're flying forward almost two decades, to something you can still buy brand new today:

- Release year: 2019.

- Summary: This thing is the best deal in music. It's a “toy keyboard” that sells for less than $100 (except, alas, in the US…), but which has the best synth-action keybed we've ever used on anything, period; it has USB MIDI, can be powered by USB, and can also be powered by batteries with battery life worthy of 2025, not 1995; it has a very fun selection of features (phrase recording, arpeggios, motion effects) that can be layered with eachother; it has a nice selection of built-in sounds; and it's the perfect thing to throw in a bag and pick up and play anywhere, any time. Genuinely, if you have even the slightest interest in music, please just buy one. We are not being paid to say this. It does of course come with compromises, but it is unfathomably good for something in its price class. The keybed is so good because it's from the highly regarded (and five times as expensive) Yamaha Reface series, by the way.

- Am I supposed to have heard of this thing? We're trying our best.

- Okay, but where have I heard it before? Oh, you haven't heard it anywhere, unless you subscribe to a certain Japanese jazz pianist's YouTube channel perhaps. He clearly loves this thing even more than we do, has the keyboardist skill to really make it sparkle, and has made a lot of very good videos about it.

- Fun fact: It has this lovely rounded shape because the designer thought of this new series of keyboards as “eggs for musicians”, as they might be the first instrument a budding musician experiences.

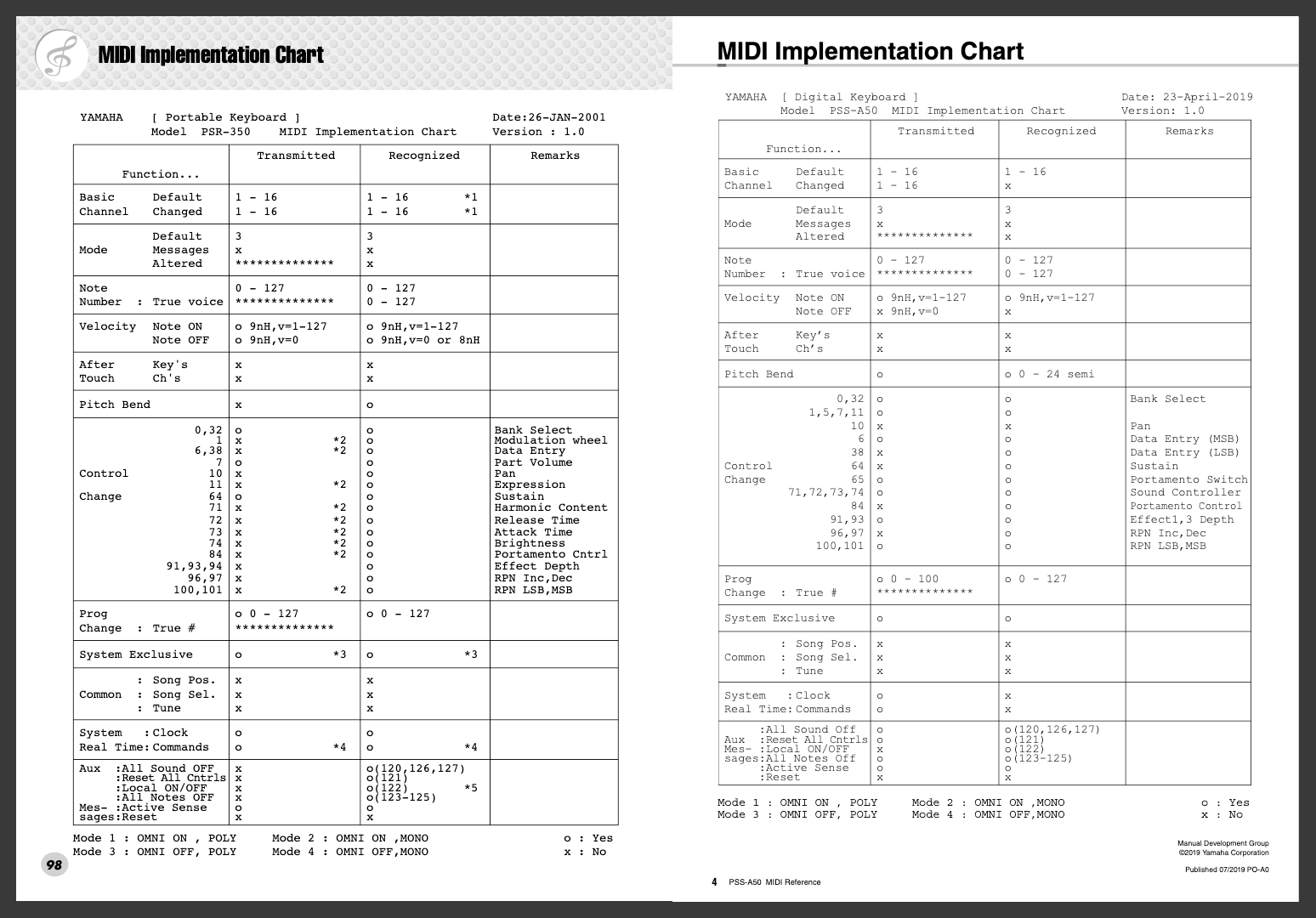

Now, this thing isn't even a General MIDI device, let alone a Yamaha XG device. The MIDI reference PDF you can download from Yamaha's website explicitly states that it is not General MIDI compliant. It can't be: the audio output is only mono, and its set of 42 instrument presets is far smaller than the 128 required by General MIDI. However, Yamaha had been making General MIDI keyboards for almost three decades when they made this, so General MIDI compliance was the path of least resistance for them. All these things are, ultimately, derivatives of the same Yamaha XG engine in one way or another. And so, yes, it has a few glaring omissions, but if you stare at its MIDI reference long enough, you start to notice it sure looks remarkably similar to, say, the PSR-350's, or that of any other Yamaha keyboard made since the late 1990's:

…it sounds like one, too. By the way, we did even get PASSPORT.MID to play back on it, but we had to make major edits to the MIDI file, which is cheating. :)

Same 3.5mm cable thing as with the SC-88VL case, except with the PSS-A50. The MIDI data, however, was sent over the PSS-A50's micro-USB port (which also powers the device); it doesn't have a traditional MIDI port on it.

This thing has a pretty high, static noise floor (the volume control is only digital), so setting the master volume high enough to make the noise level reasonable, but low enough not to clip, is quite important. I believe we set it to 10 (max is 15) in this case.

(click here only if you want to read gnarly signal chain details)

One more thing…

Finally, a bonus fun fact. Some of you may have noticed that the PSR-350 has a floppy disk drive. So you can of course put a random MIDI file on a disk, and:

It never gets old.

Conclusion

Thank you very much for reading. This post took three full days of hard work to write, but in a sense it took three years, because it's the product of a lot of persistent curiosity over that time, and we've never been able to express it well until now. If it sparked your curiosity, or clarified some things, or at least was just fun to read, then that's all we could have hoped for. We hope it wasn't too long. If you have been using a screen reader or similar, we particularly hope you appreciated the detailed hand-written descriptions of every last photo and screenshot. They say a picture is worth a thousand words, but the mean in this blogpost was actually a hundred, apparently.

We are particularly indebted to all our friends and acquaintances in the “DTM MIDI Central” Discord server, to whom we owe much of our knowledge and passion for music, and who we are repaying by running a wiki for them. If this post has given you a taste for General MIDI sounds, then you may want to check out the various DTM MIDI Central collab albums, and not just because some of them feature our (not particularly good) contributions!

We should also give a shout-out to the venerable Video Game Music Archive (vgmusic.com), the @OnlyMIDIs Twitter account, Ichigo's Sheet Music, shingo45endo (a researcher into old General MIDI devices: Twitter, GitHub), kuzu (author of the Sekaiju MIDI editor), psrtutorial.com, and many other people and resources we are likely forgetting right now. Only some of these resources were directly used in preparing this post, but they've all been important enough to us over these last three years that we need to properly thank them somewhere, and this is a good place to do it. We are also of course very thankful to Roland and Yamaha for keeping the full documentation of ancient products online even in 2025, and to everyone who tries to keep old hardware and software working, with the DOSBox project and the Win32 heroes of Microsoft and WINE being especially deserving of thanks here. This post would not be possible in a purely App Store world.

Finally: why did we actually write this post? We had almost forgotten, because we've spent far too long writing, to the point it was seriously affecting our health. But after spending a while outside, looking at the sky and thinking about nothing in particular, we remember again. A few days ago, a very close friend of ours who is an incredibly talented musician asked us if we perhaps recognised a Roland piano tone in the soundtrack of the 2010 visual novel Wonderful Everyday ~Diskontinuierliches Dasein~ (more often known as SubaHibi, an abbreviation of the Japanese title). That's a game very close to our heart for a great many reasons, not least of which the soundtrack: Yoru no Himawari and Oto ni Dekiru Koto are particular favourites, and those are both tracks where the piano takes centre stage.

Unsurprisingly, it wasn't one of the 1990's Roland piano tones we knew well; in other words, it wasn't one of the piano tones we've talked about in this post. It was simply far too high-fidelity to be from that era and category of product. If it is from a Roland product, it's probably from the mid-to-late-2000's, and most likely some kind of digital piano — a very serene kind of digital instrument that, rather than trying to be 128 instruments at once, tries to be very good at just one. Digital pianos have been so successful that it is easy to forget Roland weren't always a big name in the world of pianos; unlike Yamaha, Roland never made acoustics (as far as we know, anyway).

In the end, we didn't figure out what specific Roland product it was from. But we did remember a 2010's Roland product that had similar enough (and very beautiful) piano sounds, and that led to our friend realising Roland were just sampling a Steinway Model D, a piano first made in 1884 that needs no introduction to a concert pianist, because it's the concert grand piano.

And at that point, perhaps it doesn't even matter which product it was, right?

Live happily.

(© KeroQ 2010)

Footnotes

* We know that the fact we have suddenly started using “we”, “us” and “ourselves” in our posts must come off as jarring, considering that previously we only used “I”, “me” and “myself”. To answer the obvious questions: Yes, this blog is still written only by hikari_no_yume, who is still a single “human being”, still a “magical girl on the internet”, and still reasonable to refer to with “she”; Yes, “we” refers to hikari_no_yume unless context would indicate otherwise; Yes, it has something to do with the recent mental health crisis we are thankfully mostly through with, but this change has been a long time coming; No, we're not currently insane; No, we won't explain in further detail here for now; No, this isn't the “royal we”, and we do not like how arrogant it sounds if you read it that way, but what can we do? If you wonder why we even bother, when writing “I” would be simpler, it is alas because we, like most artists, write things both for ourselves (the authors) and you (the readers), and unfortunately there is quite a heavy significance to this change for us. That is all. 🔝 Return to text